We’re back with a new episode of “Complicated Characters of the North Isle.” Because the NorthIsle has a bunch of them.

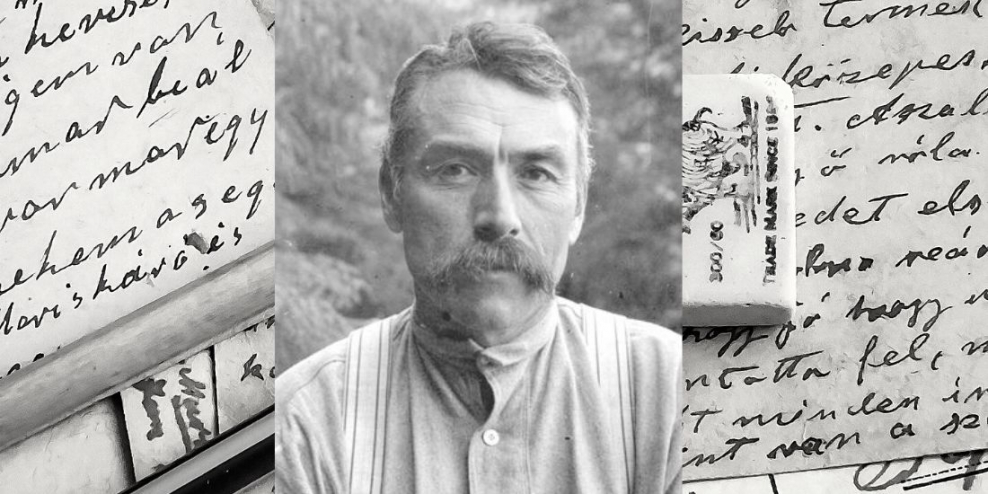

Today’s main character is George Hunt.

Like most memorable main characters, he was far from a simple good guy in the story.

This made him a villain to some and a hero to others during his time. But it makes him infinitely more interesting to learn about now.

Grab some popcorn, and let’s get into it.

His story begins in 1854 at Fort Rupert, BC. It was a trading post and Kwakwaka’wakw (known at the time as Kwakiutl) settlement.

His father, Robert Hunt, was a Hudson’s Bay Company fur trader.

Like many traders at the time, he’d been encouraged to marry an Indigenous woman to improve trade relations at the time.

He did just that, marrying George’s mother Ansnaq, (Mary Ebbett), a Taantakwáan (Tongass) woman of the Tlingit Nation.

Together, they raised George, in boyhood, known as Xawe, within the Kwakwaka’wakw settlement. Hunt spoke both English and the Kwak’wala language. Growing up within this culture set the basis on which George would found his entire career.

While George had mixed heritage, he passed as white and saw himself as such. This provided him with an huge advantage at the time, which he used to the fullest.

There’s no question that George cared for the cultures he was born and raised in. So we’ll focus on the good he brought to the political landscape of the time first.

Twice married to Kwakiutl wives, Lucy and later Francine, Hunt was deeply entrenched in the culture. His sons even fell heir to the seats of several high-ranking Kwakiutl chiefs. Through this, he was intimately familiar with the practices, rituals, and day-to-day activities of the Kwakiutl.

In fact, missionaries and government authorities saw Hunt as too deeply enmeshed in Kwakiutl life. They frequently warned him about his involvement in the banned potlatch and winter dances.

He was even arrested and tried for his participation in a “dance against the Law” at one point.

Despite this, Hunt, of course, was not Kwakiutl by birth, upbringing, or self-identification. And when he chose to use his knowledge of the culture, it was most often for personal gain.

His career started off fairly standard for the time. At just over 10 years old, he’d followed in his father’s footsteps and started working in the fur trade for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

His work mainly revolved around buying expeditions to native communities. As the fur trade declined, he acted as an interpreter and guide for missionaries and travelling colonial officials.

Through this, he met the province’s superintendent of Indian affairs, Israel Wood Powell. This event marked the beginning of a new career, one he would pursue for the rest of his life.

What was his new career? Finding and selling Indigenous artifacts.

It’s a controversial practice today, but Hunt was almost too good at it.

Hunt became one of the principal collectors of ethnographic objects from the region. He collected masks, clothing, hunting and fishing equipment, carpentry tools, dishes for feasts, and everyday eating implements.

George Hunt was partly or fully responsible for every collection of Kwakiutl cultural materials that were assembled in the world’s museums during his lifetime. That includes exhibits of over 1,000 items that are still housed at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Milwaukee Public Museum in Wisconsin now.

That’s a lot of artifacts.

His work was both a preservation of culture and a destruction of it.

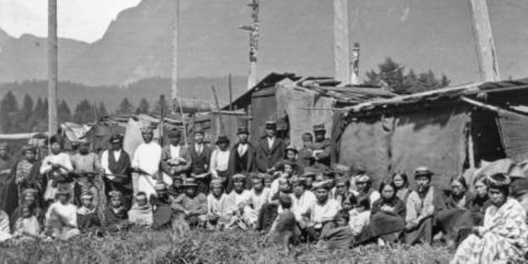

In 1893, Hunt helped create an exhibit about the Kwakwaka’wakw for the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Hunt collected hundreds of artifacts for the exhibit, travelling to Chicago with a group of 17 Kwakwaka’wakw volunteer performers.

Hunt erected a mini village at the fair, in which performers demonstrated ceremonial dances, arts, and other traditions.

The exhibit, along with many others of the time, was looked at by most viewers as a “spectacle.” Instead of opening people’s eyes to the rich and complex history of Indigenous people, it may have just reinforced bad stereotypes.

But the Kwakwaka’wakw and Hunt didn’t see it that way. They were using it as a way to declare their cultural persistence and show their political defiance against colonization.

So maybe, in that instance he had good intentions. But at other points in his life, he used debauchery to get what he wanted.

One of these moments was his “acquisition” of the Yuquot Whalers’ Shrine (or Washing House) from the Mowachaht band of the Nuu-chah-nulth (Nootka) people.

He described it as “the best thing that I ever bought from the Indians.”

The shrine was a place of great spiritual significance. It was a burial place for chiefs and was used for certain hunting rituals. The shrine included 92 carved wooden figures and 16 human skulls.

Hunt travelled to see it, and was at first refused by the shrine’s guardians.

So, to gain access, Hunt did the “obvious.” He pretended to be a shaman.

To prove that his claim was true, he had to “heal” a man who was very ill.

Luckily for Hunt (and the patient) the sick man survived the night. Hunt was granted brief access to the shrine.

He took a photo inside the shrine, and took it back to his “partner in crime,” German-born American anthropologist Franz Boas.

Boas badly wanted the shrine for his “collection.” Hunt was sent back to negotiate for its removal to the American Museum of Natural History where Boas was a curator.

After a reported exchange of $500, Hunt dismantled the centuries-old Yuquot Temple. He hastily packed the carved human figures for shipment to the museum.

There they would sit in a dusty box until this day, never even put on display. The Mowachaht are still trying to get their artifacts back.

Besides Hunts exploitative work, his writings of Kwakiutl culture are incredibly detailed. His insights into their world at the the time were regarded by some as blatant appropriation.

Boas most often published the work under his own name. Boas presented Hunt’s texts as the product of a Kwakiutl mentality, embodying “the culture as it appears to the Indian himself.”

But Hunt’s writings are full of conflicting perspectives. On the one hand, they’re the views of a resident outsider employed to conduct research who did not consider himself “Indian” at all. On the other hand, they sound like a man who, by choice, had nearly become a cultural member of the Kwakiutl.

He focused on procedural detail in everything he wrote. Though he wrote about a range of topics, his style wasn’t so much about cultural significance. It was as if, to the end of his life, he focused on the rules he had to learn to participate in Kwakiutl life.

Hunt wrote as many as 10,000 manuscript pages in Kwak’wala with English written in between the lines. He covered everything from myths and family histories to carpentry and cooking methods. Most of what he wrote was well researched, and he had consulted Elders on most topics.

Eleven manuscripts were published by Boas, and despite the detail, they were shaped as much by Boas’s research agenda as by Hunt’s own perspective and interests.

Whether Hunt’s passion for preserving (or profiting from) Indigenous culture had a positive or negative effect is not really up for debate. It did both.

His work had butterfly effects in all different directions, and really can’t be simplified as all bad or good.

It reflects much of the conflicting views he was taught and identities he as a person was grappling with throughout his lifetime.

For example, regarding shamanism, he wrote, “Sometimes I believe, and sometimes I do not believe.”

He was a human who often likely had good intentions and sometimes poured his morals down the drain. In that way, he’s not much different from us today.

All we can do is learn from the good and try not to repeat his mistakes.

What do you believe? Was George Hunt a villain or a hero? Let us know in the comments.