There are many things we do because we’re supposed to, but without really thinking about it. Like sending our kids to school wearing orange shirts on Orange Shirt Day. But this one matters.

Especially on the eve of the first annual National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

It’s been a hard year.

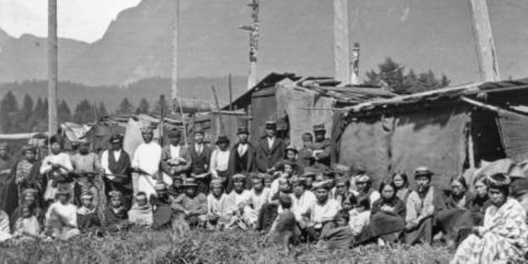

In late May, the Tk’emlúps te Secwépemc First Nation confirmed the discovery of more than 200 potential burial sites on the site of a former residential school in Kamloops. Shortly after, Parliament approved the creation of a new statutory holiday to be observed every September 30th.

Weeks later, the Cowessess First Nation announced the finding of 751 unmarked graves at a cemetery near the former Marieval Indian Residential School east of Regina. Since then, more than 300 other potential burial sites have been identified. Now searches are underway at locations across Canada.

These horrifying discoveries shine a spotlight on how far we still need to go along the path of truth and reconciliation with Canada’s indigenous people.

We need to bring justice to residential school survivors. We need to bring justice to the families of those children who died under the care of the Canadian government. We need to bring justice to those that died at the hands of the priests and nuns that ran the Catholic and Anglican church-run schools. Finally, we need to fix the inequities in our society that allow residents of some Indian reservations to live in mould-ridden substandard housing and without safe drinking water.

That’s why the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation needs to be more than a day off from work or school. It must be a call to action.

Similarly, Orange Shirt Day must be more than a mindless ritual – we owe it to residential school survivors.

In 1973, a then-6-year-old Phyllis Webstad, of the Stswecem’c Xgat’tem First Nation went to St. Joseph’s Residential School for her first day. Immediately she was stripped of a shiny orange t-shirt with a laced-up front that her grandmother had bought for her. Webstad would have had no way of knowing that this childhood trauma would be the symbolic foundation of a national movement.

The idea for Orange Shirt Day emerged from the St. Joseph’s Commemoration Project and Reunion in Williams Lake in May 2013.

Though it started humbly, the event has taken on significance for Canadians coast to coast-to-coast.

The date, September 30th, was chosen for two reasons. First, because it’s the time of year when children were forcibly taken from their homes and sent to residential schools. And second, because it’s an opportunity to set the stage for anti-racism and anti-bullying policies for the coming school year.

Now the Canadian government has formalized this event as a national holiday, the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

It’s a stat holiday that’s more than a day off from the grind.

It’s a national occasion for soul searching, but nice words simply aren’t enough, and action is really all that counts.