In 1988, an Indian author named Salman Rushdie wrote a book. That’s what authors do, right? They write books. Only this book made the Supreme Leader of Iran so mad that he put a bounty on Rushdie’s head.

The Supreme Leader of Iran was pretty extreme. Ten years earlier, he led a revolution that turned Iran from a secular country into one that was entirely Islamic. The country changed overnight. In 1988 he said Rushdie’s book was anti-Islamic. Then he told all Muslims that it was their sworn duty to kill Salman Rushdie.

And ever since then, the most extreme Muslims have tried to do just that. Iran’s governments have moved on, but the extremists have not.

Rushdie was a normal guy. He wasn’t even from Iran. To be fair, his book said some pretty racy stuff about Islam. But here’s the thing—Salman Rushdie is also Muslim.

Okay, but what does all this have to do with Alberta and Jason Kenney?

Alberta isn’t Iran, that’s for sure. But oil seems like the province’s unofficial religion. And Premier Jason Kenney acts like the province’s Supreme Leader. He attacks anyone who criticizes his government’s almost evangelical worship of oil. It’s a uniquely Albertan version of a Holy War.

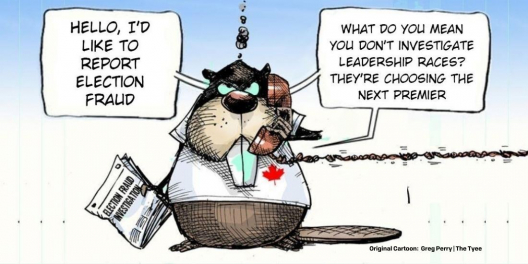

In 2019, Kenney vowed to launch a public inquiry to target the “lies and myths” of foreign-funded environmental groups. It was a central plank of his “Fight Back” election strategy. A public inquiry is the highest kind of public investigation and can have real consequences. It’s a really big deal.

Post-election, Kenney launched that public inquiry. He wanted to escalate his Holy War. So he hired Steve Allan—a forensic accountant with deep ties to Kenney’s United Conservative party—to lead the inquiry.

Now, after almost 28 months, four missed extensions, $3.5 million in Alberta’s money wasted, and a couple of dozen embarrassing scandals, Commissioner Allan has released his inquiry’s report.

The report slaps an “anti-Alberta” label on 37 environmental groups. It claims that, over the past couple decades, more than a billion dollars came in from outside Canada to fund these groups and their “Anti-Albertan Activities.”

“Anti-Albertan Activities” is just code for anything that challenges oil.

For a Canadian politician to use the power of their government to go after environmental groups that are legally exercising their democratic rights is scary. Although he never explicitly suggested violence, Kenney used coded language to basically put a bounty on the people who work for these groups.

Like the Supreme Leader’s bounty on Salman Rushdie, Kenney’s attacks on environmentalists have had real-world impacts.

The staff of many of these 37 groups—especially the women staff—have started getting racist, violent, sexual threats from the most extreme oil worshippers. The toxic threats of beheadings, hangings, assassination by snipers, rape, and sodomy have rolled in.

Strangely, 18 of the targeted groups are based in—or have a big chunk of their operations in—BC. Only three of the 37 groups have staff in Alberta.

Comissioner Allan’s conclusion after examining the targeted groups’ activities over the past decades? He found nothing “in any way improper or constitutes conduct that should be in any way impugned.”

So wait, these groups are all labelled “Anti-Alberta” but they did nothing wrong? That doesn’t make any sense.

What did the BC groups actually do?

They protected BC’s magnificent but threatened Orca whales and salmon. They studied and advocated for the rare spirit bears and wolves of the Great Bear Rainforest. They engaged in decade-long campaigns to phase out floating Atlantic salmon farms, create marine protected areas and protect Clayoquot Sound.

The Inquiry says all these activities are “anti-Albertan” even though a lot of them happened on Vancouver Island hundreds of kilometres west of the Rockies.

Why?

Because Kenney and Commissioner Allan believe somehow they interfere with Alberta’s plan to massively ramp up its oil exports.

So maybe it’s a stretch to compare the bounty on Rushdie’s head with Kenney’s witch hunt disguised as a public inquiry. But there are some similarities that should make us all uncomfortable.

Both of them demonize people who have taken a stand against a government’s core ideas.

Both of them rile up their most extreme supporters to harass people who they see as their enemies.

Both created a situation where those extreme supporters feel justified to use or threaten violence.

Now, we understand that promoting oil has been the primary job of Albertan politicians for a long time. We know that worshipping oil is Alberta’s unofficial state religion.

We also get that environmental groups can be annoying. They can be elitist, preachy know-it-alls who ignore how hard it is to just get by and feed your kids.

But whether you like or agree with environmental groups is not the point.

The point is that Canadian politicians and governments should not be allowed to use a full-blown public inquiry to attack their critics. And they should not be allowed to use that inquiry to get their extreme supporters to threaten their neighbours.

The Globe and Mail agrees. Their editorial called Kenney’s inquiry “a McCarthy-esque misuse of power.”

It’s just un-Canadian for politicians to go after critics by (ab)using their government power. It’s un-Canadian to make your political supporters think it’s okay to get violent with people who don’t agree with them.

And it’s dangerous, too. Because Alberta’s government could change. Kenney could lose the next election.

But ideas have a way of sticking around. Like the extreme Muslims who still want to kill Salman Rushdie, the extreme oil supporters may still want to mess up environmentalists long after the rest of us have moved on.