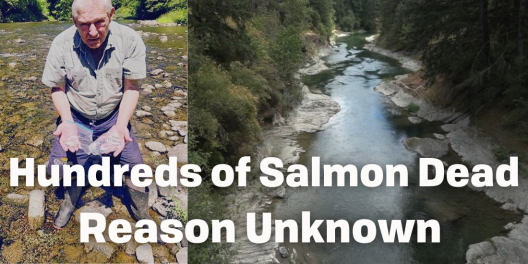

Salmon are having a really tough summer. There’s been hardly any rain, and the June heatwave was brutal. As the drought drags on, the creeks get dry, and salmon have nowhere to go.

The real shame is that Coho salmon were looking really good in the spring, at least in the Tsolum.

Caroline Heim is the program coordinator of the Tsolum River Restoration Society. She told Braela Kwan of the Narwhal that 2021 was shaping up to be a good year.

“Then the heatwave came,” she said.

Temperatures in the Tsolum got as hot as 27–29 degrees Celsius. That’s too hot for salmon, even the baby ones that do better in the heat. So the fry started to die.

“It’s hard to quantify how many died. A conservative estimate would be at least half, but probably much more than that,” Heim told Kwan. “It’s pretty dire.”

She says many of the fish that survived the heatwave are unhealthy. They have fin rot and other diseases from heat stress.

Now, all of Vancouver Island is at drought level 5. That’s the highest rating we have. It’s like an F5 tornado, or an earthquake that’s a 9.5 on the Richter scale. Only with a drought, the emergency is long and boring. We all wait for rain while the grass gets brown and hope there’s enough water to put out any fires.

But for salmon, it’s a different story. For them, the emergency is right now.

Drought hits salmon in a few ways.

1. Heat

Less water in the creek means it gets hot faster. Think of it this way—a puddle gets hot way faster than a swimming pool. So when the river isn’t flowing, and the creek is low, that water quickly gets too hot for salmon.

2. Migration

Salmon swim. They swim far to spawn. But it’s hard to swim when there’s no water. And the lowest water levels happen at the end of the summer when salmon are trying to migrate upstream.

Low water means mature salmon can’t get to their spawning grounds, which means fewer baby salmon next year.

3. Hiding places

Tiny salmon fry hide in gaps between rocks and woody debris along the sides of rivers. The water there moves a bit more slowly so they can rest and find food. But when the water is low, those hiding places disappear. As a result, the fry become an easy snack for predators, and fewer make it to the ocean.

The creeks and streams in the Comox Valley have a harder time with drought because they’re already pretty small. VanIsle doesn’t get much rain in the summer anyway. And the glaciers that used to keep the streams flowing are shrinking because of climate change.

There are things we can do to help, though.

We can learn from projects in the Cowichan Valley. Farmers, towns, and First Nations along the Koksilah River are working together to use less water there. That leaves more water in the river for fish.

The Koksilah project was made possible by BC’s Water Sustainability Act. With more funding and support from the province, groups along Comox Valley creeks could come up with their own water sustainability plans.

After all, we know our creeks the best. With a little funding and some hard work, we could figure out how to help salmon the next time a bad drought hits.

Special thanks to Braela Kwan’s Narwhal piece ‘It’s pretty dire’: Vancouver Island salmon under threat from climate change-induced droughts published on August 20, 2021.